Public Health Approaches to the Toxic Drug Crisis

FOREWORD

In May 2014, the Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) published “A New Approach to Managing Illegal Psychoactive Substances in Canada” in which it supported the development of public health approaches for addressing the needs of people who use illegal psychoactive substances. That paper emphasized that prohibition and criminalization were not achieving the goal of reducing drug use or its harms, and proposed a path forward for a public health approach that would improve outcomes.

A decade later, amid Canada's ongoing toxic drug crisis, it is imperative that governments and stakeholders come together, setting aside ideological differences to take immediate, evidence-based action. Preventable deaths due to toxic drugs continue to claim lives across all walks of society. This position statement calls for unified efforts, focusing on pragmatic solutions that prioritize saving lives over political divides. By embracing the entire continuum of interventions—from primary prevention to harm reduction to treatment—we can build a more compassionate, effective response that reduces deaths and fosters the dignity and well-being of all.

A Note on Terminology

The terminology used in the substance use lexicon has evolved over time and different stakeholders use different terminology. For the purposes of this paper, we use ‘toxic drug poisoning’ to refer to both fatal and non-fatal events. We use ‘unregulated supply’ to refer to currently illegal psychoactive substances obtained through the illicit market. We use ‘treatment’ to refer to voluntary treatment for substance use disorder, not encompassing involuntary treatment. We also note that some advocacy groups substantially reject the larger framing of problems, disorders, and identities related to substance use that underpins the terminology used in this analysis and other mainstream policy discussions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

CPHA calls on the federal government to:

- Support greater research and disaggregated data collection on population groups differentially affected by the toxic drug crisis, in order to inform targeted and culturally appropriate forms of harm reduction and treatment.

- Fund independent assessment of the successes and challenges of harm reduction interventions in relation to neighbourhood impacts, delivering operational recommendations to be mandated and monitored at the provincial/territorial level.

- The federal government and stakeholders should begin consultations on the goals and principles of a coherent regulatory approach to psychoactive substances that centres a public health approach.

CPHA calls on federal, provincial and territorial governments to:

- Develop and implement policies and programs related to substance use in ways reflecting the principles in CPHA’s policy statement ‘Framework for a Public Health Approach to Substance Use’. These principles include involving people who use drugs in all phases of policy, program and resource development.

- Fund and support the operation of harm reduction services tailored to the needs of specific populations and locations. This includes community-led organizations that effectively serve those populations in ways tailored to their needs.

- Invest in the conditions that protect people against problematic substance use. These include housing, income supports, physical and mental healthcare, and social sector supports to reduce the impact of adverse childhood events and trauma.

- Ensure that Indigenous health authorities have long-term, adequate, and stable funding to support Indigenous persons’ access to Indigenous-designed programs and services – with appropriate standards, evaluation, and data collection as well as a qualified workforce – that are accountable to Indigenous communities and available to Indigenous persons wherever they live.

- Decriminalize the possession of currently illegal psychoactive substances for personal use with evidence-based thresholds, designed in consultation with people who use drugs, community members, and law enforcement agencies.

CPHA calls on provincial and territorial governments to:

- Expand the delivery of evidence-based school programming with proven significant impact on preventing or delaying youth substance use, as well as youth-focussed education about harm reduction options.

- Set standards for the delivery, monitoring, and evaluation of a range of voluntary and evidence-based substance treatment programs, tailored to the needs of specific populations and locations.

- Work with their health systems to scale up diverse modes of prescribed safer supply programs suited to the needs of various populations in various locations. They should also work with physicians and nurses colleges to advance professional guidance for safer supply prescription.

- Develop models for alternative non-medical safer supply programs, designed with stakeholders including Indigenous governance and health authorities as well as organizations representing people who use drugs.

INTRODUCTION

[D]ead people don't recover. You also have a lot of people who use substances who don't struggle with an addiction. With the risk of the contaminated drug supply that's on our streets today, first-time substance users, intermittent substance users, casual substance users and people who struggle with addiction—people from all walks of life who use substances—are at severe risk of death.

- Guy Felicella (House of Commons, 2024a)

Many facts about the toxic illicit drug crisis in Canada are widely agreed on. It is rooted in homelessness, poverty, untreated pain, trauma, mental illness, and the persisting effects of colonialism on Indigenous Peoples, as well as many decades of failed prohibitionist and criminalizing drug policy. From its origins as an opioid crisis, it has grown in scope and harms with the advent of new synthetic drugs and additives, which mean that the unregulated supply contains substances of unknown content and potency. With fentanyl, benzodiazepines, and stimulants now found in the illicit supply across Canada (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2024a), each act of consumption brings an acute risk of overdose, injury, or death.

Persons affected by this crisis include the unhoused and the stably housed, living in cities, suburbs, and small towns as well as rural and remote areas. They are in their teens, young adulthood, and middle age; some use casually and infrequently (Balogh, 2024), others daily, and may or may not have a diagnosed substance use disorder; and they are disproportionately male, Indigenous and racialized persons (Wallace, 2024), and men working in trades (Government of Canada, 2024a). Given that an estimated 225,000 people use illicit drugs in British Columbia (BC) alone (BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel, 2023) and that 3-4% of all Canadians report using illicit drugs (Statistics Canada, 2024), it is evident that well over a million lives are at risk from toxic drug poisoning each year (Fischer et al., 2018).

There is general agreement on the medium- and long-term upstream measures needed to address this crisis. They include massive investment by governments in substance use harm prevention, health and social services, housing, income supports, and fulfilling the Truth and Reconciliation commitments to Indigenous Peoples.

Where agreement breaks down, however, is around the issue of how governments should act right now to deliver policies and services that lower the risk of death and injury for people who currently and may continue to use unregulated drugs. Some of this disagreement exists because the evidence base for addressing these problems is incomplete and the solutions complex. However, much of it stems from stigma against illicit drugs and those who use them, political leaders’ ideological positioning against sanctioning illicit drug use, and public pressure to lessen the visible impact of this crisis on downtowns and neighbourhoods. Combined, these factors mean that “harm-reduction strategies remain controversial throughout North America despite overwhelming evidence that these interventions are pragmatic, effective, and necessary” (Tyndall & Dodd, 2020).

Today in some regions of Canada and within some governments and parties, the consensus on ‘acceptable’ interventions is shrinking to include only prevention and treatment, with most harm reduction measures viewed suspiciously or rejected outright. This latter approach, however, rests on an inaccurate premise that recovery will be a lasting outcome of treatment. In reality, substance use disorder is a chronic and relapsing condition that often requires many attempts to treat, and that requires the ongoing availability of harm reduction options in case remission turns into relapse.

This is just one of the reasons why reducing available forms of effective harm reduction places people who use unregulated drugs at greater risk of toxic drug overdose death and injury. Some of these at-risk people are occasional or recreational users who do not have substance use disorder; about a third of recent opioid-related deaths in Ontario fall into this category (Gomes et al., 2022). They also include people who cannot access timely treatment, those who are not ready to enter treatment, and those who find treatment ineffective; one quarter to one third of people who start opioid agonist treatment stop within the first month (Elnagdi et al., 2023). A further category of people at high risk are those in treatment or recovery who relapse into active use; relapse rates in opioid use disorder are estimated at 65-70% (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2024).

Excluding these populations from essential harm reduction measures is antithetical to public health’s valuing of the health and well-being of all population groups, and its commitment to reducing health inequities. It is also at odds with the public health principle of using policy interventions for substance use that are both based on best evidence and pragmatically responsive to existing needs and resources (Canadian Public Health Association, 2024).

CPHA is issuing this position statement to affirm that a comprehensive range of evidence-based prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery interventions along with policy measures are necessary to address the full scope of the current toxic drug crisis and the various populations at risk. Each of these measures has its distinctive place in preventing and mitigating harms. No measure can substitute for any other, and none can be rejected while upholding the foundational commitment to value equally the lives of all persons in Canada.

The framing of this statement’s analysis reflects recent Canadian events and discourses bound up with the toxic drug crisis. These include the ongoing impacts of stigma against drug use, opposition by some communities and stakeholders to harm reduction measures, and the intensely politicized spotlight on drug policy issues amid the concurrent crises of homelessness and mental illness. Successful uptake and implementation of the policy measures CPHA recommends will be possible only if this larger political and public context is taken into account.

INDIGENOUS APPROACHES

Due to the ongoing impacts of colonization, generational trauma, and racism, deaths due to toxic drugs are far more common among Indigenous people than among other populations in Canada. Rates are as much as 5 to 7 times greater among First Nations in the provinces of Ontario, BC, and Alberta (Government of Canada, 2024b). In BC specifically, First Nations members made up 3.3% of the provincial population but 16% of toxic drug deaths in 2022 (Sterritt, 2023). Leaders of numerous Indigenous communities have declared states of emergency over the toll of this crisis on their members (Pindera, 2024).

As with Canadian society in general, there are diverse views within Indigenous communities about substance use and policies for responding to it, with communities and individuals’ perspectives on the distinct approaches of harm reduction and abstinence being shaped by communal experiences of colonialism (BC Centre on Substance Use, 2024). To navigate this complexity of views, Indigenous harm reduction advocates are using methods such as the ‘Not Just Naloxone’ program that teaches skills for having safe conversations about substance use in communities (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.), and the Sacred Breath of Life documentary series about Indigenous communities’ experience of and response to the toxic drug crisis (Indigenous Health Today, n.d.).

In their approaches to prevention, harm reduction, and treatment, Indigenous health leaders emphasize the need for Indigenous-led programming that is strengths-based and culturally appropriate. These priorities are informing Indigenous health authorities’ services in prevention, harm reduction, and treatment, as well as community collaborations with provincial and territorial governments (Government of Manitoba, 2024). National-level collaborative initiatives on substance use are focusing on priorities such as research and data collection (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2024b). Another priority is identifying, preventing, and responding to the realities of anti-Indigenous racism in mental health and addictions programming within Canadian health systems (Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, 2024).

It is critical to the success of Indigenous responses to the toxic drug crisis that an enabling policy, training, and funding environment is in place. This requires long-term, adequate, and stable funding to support Indigenous persons’ access to Indigenous-designed programs and services; the development of service standards defining performance and accountability measures for Indigenous mental health and addiction services; programs training health workers in Indigenous approaches to substance use treatment; and support for Indigenous research and evaluation grounded in and accountable to local communities (Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, 2024; House of Commons, 2024b).

PREVENTION

Discussions of the toxic drug crisis often describe prevention as the missing piece of the public health response in Canada. However, many kinds of prevention are at issue in these discussions, each with distinct goals and causal paths.

Primordial prevention aims to address the social determinants and individual risk factors linked to higher likelihood of substance use disorder and toxic drug poisoning. These include lower socioeconomic status, racism, housing instability, adverse childhood experiences, trauma, mental disorders, and the legacies of colonialism and intergenerational trauma affecting Indigenous Peoples (Alsabbagh et al., 2022; Government of Canada, 2021a; Hatt, 2021).

While public and political calls for prevention often focus on preventing the use of opioids and other substances, the scientific evidence of what is effective in this area differs considerably from common expectations of what prevention education should look like. As the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime noted in 2015, “[m]any activities labelled as drug prevention are not evidence-based, their coverage is limited and their quality unknown at best” (UNODC, 2015).

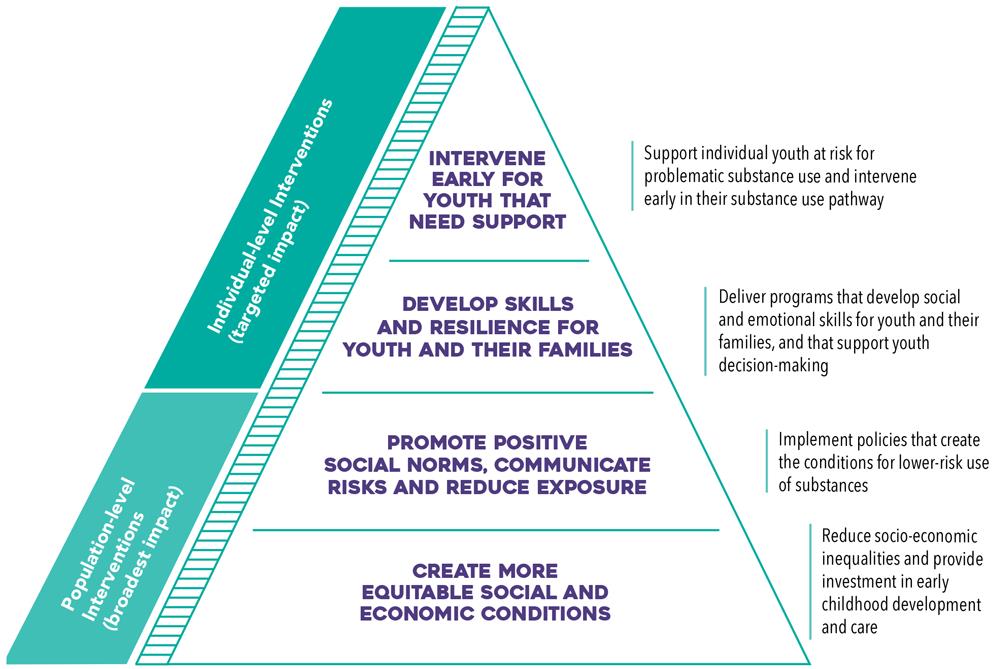

Decades of school-based and media efforts aimed at deterring youth drug use have shown that abstinence-focused or ‘zero tolerance’ programs based on scare tactics, value- or image-based messaging, and extensive education about drugs are ineffective (Haines-Saah, 2023; Fischer, 2022). Some universal prevention programs aimed at reaching youth in school or community settings do have some evidence of modest impact in delaying drug use and preventing harm. However, these programs do not address drug use per se but instead focus on developing youths’ emotional and social skills, and strengthening family and community connections (Babor et al., 2018).

These various preventive interventions are summarized in the following schematic:

Entirely preventing youth experimentation with substance use is an unrealistic goal. In the context of the toxic drug crisis, it is therefore particularly important that youth prevention efforts also include ‘safety first’ education aimed at avoiding harm for youth who do not abstain from substance use. This should include honest science-based information about risks, an understanding of legal and social consequences of experimentation, the prioritizing of safety through personal responsibility and knowledge, encouragement to delay experimentation until adulthood, and harm reduction measures for safer use (Government of Canada, 2021b; Haines-Saah, 2023).

TREATMENT

Substance use disorder is currently considered both a chronic, relapsing condition and one from which people can achieve long-term remission via effective treatment and follow-up. For persons with a substance use disorder who want to reduce or stop their use of opioids and other substances, a range of treatments is available. No single treatment works for everyone, and for some people no form of treatment is effective to eliminate or reduce their problematic substance use. Various treatment options may work for people according to the severity and complexity of their substance use disorder, their other health and social circumstances, their cultural backgrounds, and their own motivations and goals.

Research does not support the effectiveness of involuntary addiction treatment in reducing substance use and harms among people who are not willing to enter treatment (DeBeck & Kendall, 2024a; Pilarinos et al., 2018; Werb et al., 2015). Indeed, there is considerable evidence suggesting that it actually produces harms including increased risk of post-treatment fatal overdose, damaged relationships, and less willingness to engage with institutional health and social services (Ledberg & Reitan, 2022; BC Representative for Children and Youth, 2021; O’Brien & Hudson-Breen, 2023).

Evidence-based modes of voluntary treatment include community settings, day treatment programs, and residential (or inpatient) treatment centres and larger facilities using stays of weeks to months. Components of treatment may include individual and group counselling or therapy, mutual aid groups, mindfulness, exercise, and more (CAMH, 2024). Treatment program models vary substantially across Canada (Hodgins et al., 2022), and different modes will best suit persons with different histories and needs.

The current standard of practice for opioid use disorder treatment includes the use of opioid agonist therapy (OAT), which prevents withdrawal symptoms and minimizes cravings. Combined with health and psychosocial supports, this treatment typically brings “significantly improved health and social functioning and a considerable reduction in the risk of overdose and all-cause mortality” (CAMH, 2021).

The most high-profile issue with substance use treatment is its inaccessibility. As need vastly outstrips the availability of residential and community-based options, the current options for treatment are not sufficiently accessible in matching individuals’ needs, and the fragmentation of different treatment components often results in treatment failure. This mismatch is reflected, for instance, in a 2024 report on overdose deaths in Ontario that found that the rate of engagement with the health system for substance use disorders among the group who died from overdose was high, but their engagement in treatment services much lower (Weeks, 2024). Lapses between medical withdrawal management and residential treatment services as well as other mismatches between referrals and clients’ needs leave substance users on long waitlists and at danger of relapse (Russell et al., 2021).

In addition to building new treatment facilities, provinces are trying new community-based treatment modalities, such as a confidential phone access line launched in BC offering same-day medical consultations with doctors and nurses who can prescribe OAT (Luciano, 2024). However, the provision and accessibility of social service supports to accompany the OAT prescriptions are proving challenging to scale up.

Another substantial problem with viewing treatment as the favoured response to the toxic drug crisis is that the quality of treatment provided is highly variable and often not based in best-practice evidence. A 2023 analysis of Ontario residential treatment centres for substance use disorder found not only gaps in program offerings and availability, but also a lack of standardized OAT policies across programs (Ali et al., 2023). In Alberta, where treatment centres are the centerpiece of the province’s efforts, standards for medical withdrawal management, treatment, and recovery services will not be in place until at least 2025 (Cummings, 2024). Furthermore, the widespread lack of reporting on care and tracking of medium-to-long term outcomes weakens transparency and evaluation of treatment centre staffing and programming (Smith, 2024). This lack of transparency is particularly concerning given the willingness of some governments to fund private abstinence-based treatment centres that offer faith-based programming instead of OAT (Thomson, 2024; Kim, 2024; Tran, 2024). Departure from best-practice treatment including OAT is alarming in light of evidence showing that abstinence-based treatment—which reduces patients’ opioid tolerance and leaves them highly vulnerable to overdose if they relapse—produces higher mortality outcomes than no treatment at all (Heimer et al., 2024).

The 2024 release of a collaboratively-developed roadmap for mental health and substance use health standardization offers promise for setting treatment on a better course in years ahead (Standards Council of Canada, 2024).

Growing governmental commitment to treatment is an important part of a public health response to the toxic drug crisis, but it cannot be an exclusive one or prioritized at the expense of others. While treatment enables long-term recovery for some people, many others are not ready to enter treatment, are unable to access treatment that works for them, or eventually relapse into active substance use. As well, people who use drugs but do not meet the criteria for substance use disorder are not candidates for treatment. It is a fundamental concern of public health professionals to ensure that options are in place to reduce the risk of death and injury for all people who consume drugs from the unregulated supply.

HARM REDUCTION

Obviously, treatment can't be the only solution. People have a wide range of needs and different substance use journeys. They may face delays or barriers in accessing services, or they may not be ready. Meanwhile, harm reduction strategies are needed to protect them…. It sometimes takes several attempts at rehabilitation and treatment, as well as several relapses, before a person can recover. During these relapses, harm reduction strategies are needed. Moreover, in terms of treatment, no substance or pharmacological option can replace all the drugs currently on the market. Under these conditions, it can be much harder for some people to access treatment or stop using. They have few alternatives, so we need to protect them.

- Dr. Mylène Drouin (House of Commons, 2024c)

From a public health perspective, harm reduction is an interconnected “area of research, policy and practice that centers the experiences of people and communities who use substances” (Haines-Saah & Hyshka, 2023). It focusses on what people who use drugs need to stay alive and live well; it provides resources to people in ways and places that meet their needs; and it advocates for policy reforms in law, health, and research that will both support those goals and reduce harms from both substances and the policies governing them.

Harm reduction recognizes a spectrum of substance use ranging from beneficial to harmful, aiming to save lives and reduce potential harms without assuming that reduced use or abstinence are necessary goals for individuals or institutions. It is also a pragmatic approach, recognizing that substance use cannot realistically be eliminated but that evidence-based harm reduction is possible and is consistent with “protect[ing] and promot[ing] the health of individuals and communities” (CPHA, 2024).

Research demonstrates the positive impact of harm reduction programs for people who use drugs, not only in preventing injury and death but also in connecting them to services that may increase their likelihood of seeking treatment (Moran et al., 2024). Evidence also suggests that such programs both are cost-effective in terms of public spending and do not cause higher rates of nearby violence or property-related crime (Moran et al., 2024).

New methods of delivering harm reduction services and supplies are being piloted in order to reach people who use drugs in rural and remote locations. For part of 2023-2024, the Fraser Health Authority in British Columbia offered an online portal where people who cannot use supervised consumption services could access instructional materials and order free customized boxes of harm reduction supplies for home delivery. The program website also provided instructional material for safer use of the products as well as information on connecting with clinical and outreach teams or virtual care (Moman, 2024). However, the range of supplies and information available was significantly restricted by the BC government in 2024 amid political controversy (Zavarise, 2024). A common model across Canada is the use of outreach vans delivering harm reduction supplies and education as well as nursing services, clothing, and referrals to other services.

More such outreach initiatives are urgently needed, as well as research on harm reduction interventions needed to serve appropriately equity-deserving populations such as women, Indigenous persons, and racialized groups (Milaney et al., 2022). As well, better harm reduction programs are needed for youth who use drugs (Kimmel et al., 2021). As noted in a 2024 expert report, structurally disadvantaged people who use drugs must be meaningfully included in developing such services, given that they are “often best positioned to identify the problems to be solved and the solutions that will work best for people with similar lived experiences” (Gruben et al., 2024).

Two of the most controversial forms of harm reduction, supervised consumption services and safer supply programs, are discussed in subsequent sections. Other harm reduction measures in use across Canada include drug checking, needle exchange, and naloxone kits for reversing opioid overdose.

NALOXONE

Opioid overdose can stop breathing, producing brain damage and death (Canadian Mental Health Association [CMHA], 2019). These impacts can be averted by one or more doses of naloxone, a safe drug that attaches to opioid receptors and blocks or reverses their effects for 20 to 90 minutes (Government of Canada, 2024c). It works only on opioids (e.g., fentanyl, heroin, morphine, and codeine) and cannot reverse overdoses caused by non-opioid drugs such as cocaine, ecstasy, or Ritalin (Armstrong, 2023). Available in both nasal spray and injectable formats, naloxone is widely used in Canada by emergency responders and bystanders, and is available for free at pharmacies, local health authorities, and some post-secondary institutions, along with training in its use. Statistics across many jurisdictions show increasing numbers for naloxone kit distribution, trainings, and their use to reverse overdose (Rukavina, 2024; BC Centre for Disease Control, 2019; Quon, 2024). As well as scaling up naloxone distribution and training, a priority measure is increasing access to its nasal spray version, which is easier and less intimidating to use than the injectable version and hence can result in faster, more effective use in reducing overdose (Culbert, 2024a; Armstrong, 2023).

DRUG CHECKING

The increasing presence in the unregulated drug supply of unknown substances and potencies is a key driver of the toxic drug poisoning crisis (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2024a). Drug checking programs enable people to determine what is present in their pills, powders, crystals, or other substances in order that they can make informed decisions on whether or how to consume them (Tobias et al., 2024). Substances can be tested at health service locations in about 10 minutes using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer, which can identify up to six substances in a drug sample, including heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, MDMA, fentanyl, benzodiazepines, and cutting agents (Fraser Health, 2024; Vancouver Coastal Health, 2024). Testing can also be done using take-home fentanyl test strips, which are small, portable, and capable of detecting fentanyl in minute concentrations (Moran et al., 2024).

Drug checking programs are now operating across Canada with proven benefits. In Toronto, for example, more than 9,000 samples were tested between 2019 and early 2023 that contained more than 400 unique drugs, many of them linked to overdose (McDonald et al., 2023). Drug checking programs have other benefits, such as acting as a gateway for people to access harm reduction services, referrals to health and social services, and treatment (McDonald et al., 2023). Drug checking programs also enable informal community monitoring of unregulated drugs by enabling buyers to make better-informed choices (Moran et al., 2024; Wallace et al., 2021). Finally, these programs enable local public health and social service agencies to be aware of trends in unregulated drug supply contaminants and issue alerts to people using these substances and service providers (Moran et al., 2024).

DISTRIBUTION OF DRUG CONSUMPTION SUPPLIES

Needle distribution programs started in Canada during the late 1980s in the context of HIV prevention. Today, there are over 30 programs operating nationwide (Canadian Addiction Treatment Centres, 2024) that provide people who use drugs with sterile supplies to prevent the spread of blood-borne infections and safely dispose of used needles. Like other forms of harm reduction services, they can build relationships between people who use injection drugs and health service providers, leading to further positive engagements in health and social services (Card et al., 2019).

Despite the positive effects of these programs, some governments have rejected them and the broader harm reduction model. In 2024 the Government of Saskatchewan stopped funding single-use pipes and needles for supervised consumption services, contending that provision of supplies and instruction ‘sends the wrong message’, i.e., that drug use is safe and condoned (Mandryk, 2024; Quon, 2024), and falsely asserting a link between distribution programs and increased overdose and HIV infection rates in the province (Salloum, 2024).

SUPERVISED CONSUMPTION SERVICES

Given that any use of drugs from the unregulated supply brings the risk of injury or death, an essential part of harm reduction is encouraging people to consume these potentially toxic drugs in a place where there are others trained to intervene with life-saving measures in the case of an overdose. Supervised consumption services (sometimes called supervised consumption sites, overdose prevention centres, or drug consumption rooms) are designated locations that provide a space to use pre-obtained drugs, with trained staff onsite (Government of Canada, 2024d). Depending on the facility’s policies and physical set-up, people can bring drugs to consume orally, by injection, by smoking, or nasally. The facilities are located in various places; some inside permanent neighbourhood facilities, others in mobile vehicles, hospitals, or outdoor tents to facilitate safe drug inhalation (Culbert, 2024b).

A major challenge, however, is that most facilities lack the equipment and set-up to support safe drug inhalation, a mode of drug consumption increasingly prevalent and highly associated with overdoses in Alberta, BC, and Ontario (Giliauskas, 2022). While the cost of installing specialized ventilation equipment is a barrier (Joannou, 2023), this gap in service provision is inconsistent with current trends in drug consumption modalities and fails to meet the needs of people who smoke drugs (Konnert, 2024; Bellefontaine, 2024).

The positive impacts of supervised consumption services in reducing overdose deaths are well established. In BC alone, they reversed nearly 29,000 toxic drug overdoses between January 2017 and April 2024 (Culbert, 2024b). A systematic review across multiple countries (including Canada) concluded that these facilities lower the risk of overdose and unsafe drug use behaviours, and increase access to treatment (Kennedy et al., 2017). A study on overdose rates in Toronto neighbourhoods revealed a 67% decrease in the overdose mortality rate following the introduction of a facility, with stronger positive effects in neighbourhoods where the facility had been operational for at least a year (Rammohan et al., 2024).

Furthermore, supervised consumption services enable people who use drugs to access a range of other services, including other harm reduction measures such as drug checking, clean drug use supplies, education in safe injection practices, and naloxone kits. They also offer infectious disease testing, referrals to healthcare and addiction treatment, and access to social supports such as housing and employment (Government of Canada, 2024d). These comprehensive services address personal needs and facilitate pathways to improved quality of life (Hyshka et al., 2021).

Despite the documented benefits of supervised consumption services, their adoption in Canada is limited. Opening and operating a facility is highly complex from a governance and funding standpoint, typically involving coordination among federal, provincial, and municipal levels of government. Both federal and provincial approval processes require that sites conduct community consultations prior to submitting their applications and continue to engage in ongoing consultations with the community once operational (Harrison, 2023).

Some residents and business owners oppose proposed site locations due to concerns about potential adverse effects on their neighbourhoods (Kolla et al., 2017). A considerable body of research from Canada and Europe has found that supervised consumption facilities do not lead to increased public disorder or crime nearby (Kennedy et al., 2017; Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, 2024). Although some communities do identify problems concentrated near facility locations (Culbert, 2024b; Lautenschlager, 2023; Ibrahim, 2024; Perry, 2024), other facilities operate without causing community concern (Woodward, 2024). While two reviews of a Toronto safe consumption facility recommended changes in the management practice to address neighbours’ concerns, they also noted that the facilities brought community value and should stay in operation (Rider, 2024). These findings have been confirmed in a separate evidence review of supervised consumption services in Ontario conducted by the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation (2024).

Ongoing independent research into the community impacts of safe consumption facilities—and other harm reduction services as well—is important to sustaining public support for the expansion of these facilities and services in Canada. These facilities are essential to harm reduction, and they will be effective only if successfully operating in places where their clients can and will access them.

SAFER SUPPLY

Safer supply programs are a form of harm reduction that aims to help persons diagnosed with severe substance use disorder avoid injury or death from the toxic unregulated supply of drugs by providing them with prescribed medical-grade pharmaceuticals instead. (While diagnosis with severe substance use disorder is not technically a necessary criterion for access, access has thus far been limited virtually exclusively to those so diagnosed.) Because it is not feasible for all users of unregulated drugs to use exclusively at safe consumption facilities, there is an absolute need for a safer supply of drugs that would enable consumption of known substances and strengths.

Safer supply contributes significantly to protecting persons from overdose death. A 2024 study of people in BC with diagnosed opioid or stimulant use disorder found that those who received safer supply had a 55% lower chance of overdose death and a 61% lower chance of death from other causes in the week following their initial prescription. These rates rose to 89% and 91% respectively for persons who accessed safer supply for four days or longer (Slaunwhite et al., 2024).

These programs improve clients’ quality of life by connecting them with social and health services through their regular contact with medical personnel. With the threats of criminalization from procuring unregulated drugs removed, and with greater control over their substance use in place, many people in these programs are able to stabilize their lives and improve their well-being (NSS-CoP, n.d.; Schmidt et al., 2023; Ivsins et al., 2021). A review of Ontario safer supply program results found positive health outcomes for participants, including: lower rates of emergency department visits and hospital admissions; lower reliance on the toxic unregulated drug supply; and lower rates of infections related to substance use. Broader positive outcomes included better quality of life and mental health, better financial stability, and less involvement in criminalized activities (Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, 2023).

Various challenges and barriers with safer supply programs need policy solutions. First, they offer a limited range of opioids and other substances (Ferguson et al., 2022), which are less potent than the substances and strengths that people have become accustomed to consuming from the unregulated supply (Ivsins et al., 2020; Harnett, 2024). For those who seek not just prevention of withdrawal symptoms but also euphoria and pain management (Pauly et al., 2022), those unmet needs lead them to turn to the unregulated supply to supplement the prescribed drugs (McNeil et al., 2022). In order for safer supply programs fully to meet clients’ needs and separate them wholly from the unregulated supply, they must offer stronger and more diverse prescriptions that address clients’ needs.

Some models of prescribed safer supply pose significant barriers for participants in requiring them to visit a health care provider or pharmacy daily to obtain or take medication. The requirement of witnessed dosing can foster a mistrustful relationship between health care providers and clients, as well as impede work and travel. These challenges highlight the need for flexible dispensing options such as extended carry-home doses, delivery of medications, and other measures to make the programs more accessible (Pauly et al., 2022). These options are particularly important for expanding programs to serve rural and remote regions.

Much of the public and political concern over safer supply programs focuses on the potential for take-home supply to be diverted willingly or unwillingly to persons other than the prescribed recipient (Larance et al., 2011). It is acknowledged that diversion does occur with prescribed safer supply medications (as with many other prescriptions), often in order to address unmet needs (Bardwell et al., 2021a; Bardwell et al., 2021b). However, there is no evidence supporting critics’ charge that such diversion is increasing overdose deaths or leading youth to become addicted (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2023; B.C. Coroners Service, 2022; BC Centre for Disease Control, 2021; Gomes et al., 2022).

A comprehensive 2023 review by the office of the BC Provincial Health Officer noted these and other challenges with the program, while also supporting the indispensable public health role that prescribed safer supply plays in protecting people who use drugs (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2023). As noted in a follow-up report, however, the prescription model can never reach sufficient scope to protect the hundreds of thousands of persons using illicit drugs in BC alone. Nor can it meet the needs of persons whose substance use does not reach the threshold of diagnosed disorder, or those who are unwilling to interact with the medical system due to experiences of stigmatizing treatment or trauma. As the report concludes, protecting these population groups at acute risk of poisoning and other harms requires exploring non-medicalized approaches for providing persons who use drugs with alternatives to the highly toxic unregulated supply. Provided that they are accompanied with rigorous design consultation, monitoring, and evaluation, non-prescribed safer supply models may be able to protect a much broader group of at-risk people while also bringing the positive benefits found in current prescribed safer supply programs (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2024).

DECRIMINALIZATION

For decades, the public health community, as well as human rights experts and grassroots advocates, have viewed criminalization as an ineffective, harmful, and unjust approach to curbing the harms of substance use and of the unregulated drug trade. As CPHA noted in its 2017 position statement on decriminalization, “the use of criminal sanctions to limit the personal use of illegal psychoactive substances has failed to limit both the number of users and the products available to them” (CPHA, 2017).

Criminalizing drug use not only is ineffective in reducing use and access, but is costly, counterproductive, and harmful (Virani & Haines-Saah, 2020). The fear of stigmatization and criminal prosecution means that people accessing the unregulated drug supply are more likely to use alone and in high-risk ways, increasing the risk of death, injury, and the transmission of blood-borne infections (Jesseman & Payer, 2018). Incarceration and criminal records cause most harm to populations at the lower end of the social gradient, through pathways such as reduced employment prospects, diminished access to suitable housing, or loss of child custody. These impacts of criminalization disproportionately affect Black and Indigenous populations (Government of Canada, 2021c; Khenti, 2014), who are already structurally disadvantaged.

For many reasons, the public health community and other stakeholders endorse removing the threat of criminal prosecution for the possession of small quantities of currently illegal drugs for personal use. By removing the threat of incarceration, a criminal record, and associated stigma, it can increase willingness to seek out harm reduction options and treatment for a substance use disorder. The public funding currently used for policing and incarcerating people who use drugs (and for addressing downstream impacts of their criminalization) could promote health more directly if used for health-promoting programs and social services.

Importantly, decriminalization should be accompanied by other policies intended to control use and limit negative impacts. As a Royal Society of Canada expert task force recently noted, decriminalization “does not represent a single approach, intervention, or model; rather it describes a range of principles, policies and practices that can be implemented or adopted by various levels of governments and stakeholders, depending on the jurisdiction and local context” (Gruben et al., 2024). A decriminalization scheme should specify which substances are affected; what quantity can be legally possessed for personal use and by which persons; where drug use is permitted and prohibited; policies for deterring harmful use; and supportive social policies and services aimed at improving the health and living conditions of persons with a substance use disorder. As the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has recently commented, the impacts of drug policy reform are dependent on the social context in which it takes place and the deterrent effect of criminalizing certain behaviours (UNODC, 2024).

From a human rights perspective, decriminalization respects the rights of persons to ingest substances of their choice—just as the current legal regime around tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis does for persons who use those substances. In extending this right to all drugs, decriminalization would begin to remedy the inequities created by currently disparate regulatory approaches. As public health advocates note, decriminalization is most centrally about social justice, in that it begins to undo the structural effects of criminal law’s infliction of disproportionate harm on persons already disadvantaged by societal inequities, as is the case for many persons with substance use disorders (Virani & Haines-Saah, 2020).

While decriminalization can reduce some harms and bring some benefits, in isolation it cannot address other dimensions of the current toxic drug crisis. It cannot make headway in reducing the toxicity of the unregulated market, treating persons with substance use disorders, providing shelter for unhoused persons, nor preventing or treating mental health disorders.

Various jurisdictions’ recent experiences with decriminalization underline the need for comprehensive policies and services to accompany legal change in order to maintain public and political support while improving outcomes for people who use unregulated drugs. In BC, the 2023 launch of a three-year trial of decriminalizing personal drug possession was substantially modified in 2024 after concerns were raised about drug use in hospitals, businesses, and parks (Berz, 2024; Hager, 2024). Given that the decriminalization pilot project did legally prohibit drug use in those places, it seems that a lack of enforcement capacity and social supports were at issue. While the more expansive initial phase of the BC decriminalization pilot did not improve the toxic drug crisis in the province overall (and could not have done so) (Berz, 2024), it did reduce drug-related encounters with the legal system while keeping use of harm-reduction healthcare resources at a stable level (BC Centre for Disease Control, 2024).

The state of Oregon reversed its 2020 introduction of decriminalization for similar reasons: lack of accompanying social service delivery, funding, and stakeholder collaboration. Amid public backlash connected to rising overdose deaths and high rates of drug use in public spaces, the state restored criminal penalties in 2024 (Davies, 2024; UNODC, 2024).

In Portugal, where drug possession was decriminalized in 2001, the ongoing public support for and relative success of this policy in producing societal benefits (Transform Drug Policy Foundation, 2021) are closely linked to its accompanying investment in health services, social services, education, and outreach (Slade, 2021; House of Commons, 2024a). Notably, it took time for this comprehensive bundle of policy measures to take effect: a 75% drop in drug-related deaths was achieved after a period of 21 years (Paun & Hernandez-Morales, 2024).

These jurisdictions’ experiences suggest that in order for decriminalization to produce gains in safety, health, and well-being for people who use drugs while maintaining public and political support, this measure must be accompanied by substantial harm reduction, health and social services, and policy measures. Introducing decriminalization in a context lacking supportive social services may undermine public and political support for that policy, particularly when drug policy is intensely politicized.

Some experts and advocates maintain that decriminalization is a necessary measure to enact immediately on health and human rights grounds, whether or not supportive conditions are in place (Gruben et al., 2024). Others believe that calling for decriminalization without the necessary services in place is premature (House of Commons, 2024d, 2024a). In the midst of a complex crisis of toxic drugs, mental illness and homelessness, renewed efforts to decriminalize drugs are needed.

TOWARD LEGALIZATION AND REGULATION

In 2014, CPHA’s position statement on a new approach to managing illegal psychoactive substances in Canada noted that the existing approach of prohibition and criminalization was inconsistent with the state of public health knowledge about the harms these approaches inflict on individuals, families, and communities as well as their failure to reduce drug use (CPHA, 2014). Just as a public health approach partially now shapes the production, manufacture, marketing, and sale of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis, it should be extended to guide legalization and regulation of certain currently unregulated substances. As advocates for a regulated safer supply note, “[w]hen we regulate a substance, we have the most control over its production, distribution and consumption” (DeBeck et al., 2024b).

With rigorous limits on commercial influence on this space, and with the scaled-up introduction of evidence-based education and prevention efforts, there is strong reason to expect that such an approach would be better for the health of many populations in Canada. A move toward a coherent regulatory approach to psychoactive substances has been endorsed in recent years by two separate expert panels examining the toxic drug crisis (Gruben et al., 2024; Health Canada Expert Task Force on Substance Use, 2021). The removal of criminal penalties for personal possession and use of currently unregulated drugs, combined with the introduction of alternative non-medical approaches to safer supply, would be a substantial step forward on the path of full legalization and regulation. Taking small steps toward these goals now—while also addressing the broader social, health, and housing context of the current toxic drug crisis—is both possible and necessary.

CONCLUSION

The toxic drug crisis in Canada demands urgent, unified action that transcends ideological divides. Governments at all levels, along with key stakeholders, must prioritize and scale up evidence-based solutions that address the immediate and long-term needs of those affected by this crisis. Harm reduction, safer supply programs, decriminalization, and culturally appropriate Indigenous-led initiatives are essential to saving lives and reducing harm. By embracing a comprehensive public health approach, we can prevent further unnecessary deaths and foster the well-being of all Canadians, ensuring that every person has the opportunity to live with dignity and hope.

REFERENCES

Ali, F., Law, J., Russell, C. et al. (2023). An environmental scan of residential treatment service provision in Ontario. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 18, 73.

Alsabbagh, M. W., Cooke, M., Elliott, S. J., Chang, F., Shah, N., & Ghobrial, M. (2022). Stepping up to the Canadian opioid crisis: a longitudinal analysis of the correlation between socioeconomic status and population rates of opioid-related mortality, hospitalization and emergency department visits (2000–2017). Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 42(6), 229–237.

Armstrong, L. (2023). Naloxone: What to know about the opioid overdose-reversing drug, free across Canada. CTV News.

Atif, S., Edalati, H., Bate, E., & Salazar, N. (2023). In-patient treatment for substance use in Canada. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

Babor, T. F., Caulkins, J., Fischer, B., Foxcroft, D., Humphreys, K., Medina-Mora, M. E., Obot, I., Rehm, J., Reuter, P., Room, R., Rossow, I., & Strang, J. (2018). Preventing illicit drug use by young people. In Drug Policy and the Public Good, Oxford University Press eBooks.

Balogh, M. (2024). Contaminated illicit recreational drugs raise alarm in Kingston. The Recorder and Times (July 17, 2024).

Bardwell, G., Ivsins, A., Socías, M. E., & Kerr, T. (2021a). Examining factors that shape use and access to diverted prescription opioids during an overdose crisis: A qualitative study in Vancouver, Canada. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 130, 108418.

Bardwell, G., Small, W., Lavalley, J., McNeil, R., & Kerr, T. (2021b). “People need them or else they're going to take fentanyl and die”: A qualitative study examining the ‘problem’ of prescription opioid diversion during an overdose epidemic. Social Science & Medicine, 279, 113986.

BC Centre for Disease Control. (2024). Decriminalization in B.C.

BC Centre for Disease Control. (2021, September 15). Knowledge Update: Post-mortem detection of hydromorphone among persons identified as having an illicit drug toxicity death since the introduction of Risk Mitigation Guidance prescribing.

BC Centre for Disease Control. (2019). Report estimates more than 590,000 naloxone kits distributed across Canada.

BC Centre on Substance Use. (2024). Addressing the complexities of abstinence-based perspectives within Indigenous communities by emphasizing cultural strengths [podcast]. Addiction Practice Pod, S. 4 Ep. 2 (Feb. 8, 2024).

BC Coroners Service Death Review Panel. (2023). An Urgent Response to a Continuing Crisis.

BC Coroners Service. (2022, May 16). Coroners Service News Release: 165 British Columbians lost to toxic drug supply in March 2022.

BC Mental Health & Substance Use Services. (n.d.). Opioid Agonist Treatment.

BC Representative for Children and Youth. (2021). Detained: Rights of children and youth under the Mental Health Act.

Bellefontaine, M. (2024). “Inhalation rooms in safe consumption sites could save lives, Alberta advocates say.” CBC News (June 12, 2024).

Berz, K. L. (2024). What went wrong with drug decriminalization in British Columbia? Those on the streets have a message for Toronto. Toronto Star.

Canadian Addiction Treatment Centres. (2024). Why is Canada’s Needle Exchange Program Important.

Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs (CAPUD). (2019, February). Safe Supply Concept Document.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2024a). Do Drugs Contain What We Think They Contain? Results from CUSP: The Community Urinalysis and Self-Report Project [website].

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2024b). First Nations, Métis and Inuit National Partnership Building Roundtable Meeting Report.

Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. (2024). Evidence Around Harm Reduction and Public Health-Based Drug Policies (website).

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2019). Naloxone Toolkit.

Canadian Public Health Association. (2024). Framework for a Public Health Approach to Substance Use.

Canadian Public Health Association. (2017). Decriminalization of Personal Use of Psychoactive Substances.

Canadian Public Health Association (2014). A New Approach to Managing Illegal Psychoactive Substances in Canada.

Card, K. G., Pauly, B., Wallace, B., Urbanoski, K., & Gagnon, M. (2019). Needle Exchange Evidence Brief. University of Victoria.

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health [CAMH]. (2024). Fundamentals of Addiction: Treatment [webpage].

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health [CAMH]. (2021). Opioid Agonist Therapy: A Synthesis of Canadian Guidelines for Treating Opioid Use Disorder.

Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation. (2024). Supervised Consumption Services in Toronto: Evidence and Recommendations. (Toronto, November 2024).

Chimbar, L., & Moleta, Y. (2018). Naloxone Effectiveness: A Systematic Review. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 29(3), 167–171.

Culbert, L. (2024a). What would you rather do? Squirt naloxone up a victim's nose or inject a needle? Vancouver Sun.

Culbert, L. (2024b). “What happens inside Metro Vancouver's overdose prevention sites — and how they're dealing with neighbours' concerns.” Vancouver Sun (Aug. 6, 2024).

Cummings, M. (2024). “Alberta should set standards for addiction treatment centres, judge says in fatality report.” CBC News (July 4, 2024).

Davies, D. (Host). (2024). Why Oregon's groundbreaking drug decriminalization experiment is coming to an end. Fresh Air [Audio podcast].

DeBeck, K., & Kendall, P. (2024a). B.C.’s plan for involuntary addiction treatment is a step back in our response to the overdose crisis. The Conversation.

DeBeck, K., Kendall, P., & Lapointe, L. “Drug prohibition is fuelling the overdose crisis: Regulating drugs is the way out.” The Conversation (July 4, 2024b).

Dellplain, M. (2024). Involuntary drug treatment: ‘Compassionate intervention’ or policy dead end? Healthy Debate.

Elnagdi, A., McCormack, D., Bozinoff, N., Tadrous, M., Antoniou, T., Munro, C., Campbell, T., Paterson, J. M., Mamdani, M., Sproule, B., & Gomes, T. (2023). Opioid agonist treatment retention among people initiating methadone and buprenorphine across diverse demographic and geographic subgroups in Ontario: a population-based retrospective cohort study. The Canadian Journal of Addiction, 14(4), 44–54.

Ferguson, M., Parmar, A., Papamihali, K., Weng, A., Lock, K., & Buxton, J. A. (2022). Investigating opioid preference to inform safe supply services: a cross sectional study. International Journal of Drug Policy, 101, 103574.

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). Not Just Naloxone Program [website].

Fischer, B., Pang, M., & Tyndall, M. (2018). The opioid death crisis in Canada: crucial lessons for public health. The Lancet Public Health, 4(2), e81–e82.

Fischer, N. R. (2022). School-based harm reduction with adolescents: a pilot study. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention and Policy, 17(1).

Fraser Health. (2024). Drug checking - Fourier-transform infrared spectrometers (FTIR).

Giliauskas, D. (2022). A review of supervised inhalation services in Canada. Ontario HIV Treatment Network.

Gomes, T., Murray, R., Kolla, G., Leece, P., Kitchen, S., Campbell, T., Besharah, J., Cahill, T., Garg, R., Iacono, A., Munro, C., Nunez, E., Robertson, L., Shearer, D., Singh, S., Toner, L., & Watford, J.. on behalf of the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario and Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). (2022). Patterns of medication and healthcare use among people who died of an opioid-related toxicity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network.

Gomes, T., Murray, R., Kolla, G., Leece, P., Bansal, S., Besharah, J., Cahill, T., Campbell, T., Fritz, A., Munro, C., Toner, L., Watford, J. (2021, May). Changing circumstances surrounding opioid-related deaths in Ontario during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, The Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario / Ontario Forensic Pathology Service, Public Health Ontario.

Government of British Columbia. (2024). Decriminalizing people who use drugs in B.C.

Government of Canada. (2024a). Men in trades and substance use.

Government of Canada. (2024b). Indigenous Services Canada: 2024-25 Departmental Plan.

Government of Canada. (2024c). Naloxone.

Government of Canada. (2024d, February 9). Supervised consumption explained: types of sites and services.

Government of Canada. (2024e, March 27). Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada.

Government of Canada. (2023, December 4). Supervised consumption sites: Status of applications.

Government of Canada. (2021a). Opioid-related harms and mental disorders in Canada: A descriptive analysis of hospitalization data.

Government of Canada. (2021b). Preventing substance-related harms among Canadian youth through action within school communities: A policy paper.

Government of Canada. (2021c). Recommendations on Alternatives to Criminal Penalties for Simple Possession of Controlled Substances.

Government of Canada. (2018). Preventing Problematic Substance Use in Youth. Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer.

Government of Manitoba. (2024). “Manitoba Government Partners with Aboriginal Health and Wellness Centre to Establish Canada's First Indigenous-Led Supervised Consumption Site.” [news release] (July 12, 2024).

Greer, A., Xavier, J., Loewen, O. K., Kinniburgh, B., & Crabtree, A. (2024). Awareness and knowledge of drug decriminalization among people who use drugs in British Columbia: a multi-method pre-implementation study. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 407.

Gruben, V., Hyshka, E., et. al. (2024). Urgent and Long Overdue: Legal Reform and Drug Decriminalization in Canada. Royal Society of Canada.

Hager, M. (2024). B.C. backs off drug decriminalization pilot project following outcry. The Globe and Mail.

Haines-Saah, R. (2023). Youth Drug Prevention 101 (webinar). Moms Stop the Harm.

Haines-Saah, R. J., & Hyshka, E. (2023). Harm reduction. In Edward Elgar Publishing eBooks (pp. 140–145).

Harnett, C. (2024). “Safer supply too weak for most street-drug users, says Island Health doctor”. Times Colonist (Feb. 8, 2024).

Harrison, L. (2023, August 28). When it comes to Toronto's supervised injection sites, who's in charge? Here's what you need to know. CBC.

Hatt, L. (2021). The opioid crisis in Canada. Library of Parliament.

Health Canada Expert Task Force on Substance Use. (2021). Recommendations on the federal government's drug policy as articulated in a draft Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS).

Heimer, R., Black, A. C., Lin, H., Grau, L. E., Fiellin, D. A., Howell, B. A., Hawk, K., D’Onofrio, G., & Becker, W. C. (2024). Receipt of opioid use disorder treatments prior to fatal overdoses and comparison to no treatment in Connecticut, 2016–17. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 254, 111040.

Hodgins, D. C., Budd, M., Czukar, G., Dubreucq, S., Jackson, L. A., Rush, B., Quilty, L. C., Adams, D., & Wild T. C.. (2022). Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in Canadian Psychosocial Addiction Programs: A National Survey of Policy, Attitudes, and Practice. Can J Psychiatry, 67(8), 638-647. doi: 10.1177/07067437221082858. Epub 2022 Mar 8. PMID: 35257596; PMCID: PMC9301153.

House of Commons. (2024a). Evidence: Standing Committee on Health, HESA-121 (June 6, 2024).

House of Commons. (2024b). Evidence: Standing Committee on Health, HESA-114 (May 6, 2024).

House of Commons. (2024c). HESA Committee Meeting 119 (May 30, 2024).

House of Commons. (2024d). HESA Committee Meeting 110 (April 15, 2024).

Hyshka, E., Speed, K., Kosteniuk, B., Kennedy, M. C., Jackson, L., & Scheim, A. (2021). Evidence brief: Health Impacts. Edmonton: Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse. 4p.

Ibrahim, N. (2024, February 22). Study sparks debate on impact of Toronto safe consumption sites. Global News.

Indigenous Health Today. (n.d.). Sacred Breath of Life: The Toxic Drug Crisis [documentary series].

Ivsins, A., Boyd, J., Mayer, S., Collins, A., Sutherland, C., Kerr, T., & McNeil, R. (2021). “It’s helped me a lot, just like to stay alive”: a qualitative analysis of outcomes of a novel hydromorphone tablet distribution program in Vancouver, Canada. Journal of Urban Health, 98(1), 59-69.

Ivsins, A., Boyd, J., Mayer, S., Collins, A., Sutherland, C., Kerr, T., & McNeil, R. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to a novel low-barrier hydromorphone distribution program in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 216, 108202.

Jesseman, R., & Payer, D. (2018). Decriminalization: Options and Evidence (Policy Brief). Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

Joannou, A. (2023, October 1). As smoking toxic drugs kills in record numbers, B.C. coroner calls for supervised inhalation sites. CBC.

Kennedy, M. C., Karamouzian, M., & Kerr, T. (2017). Public health and public order outcomes associated with supervised drug consumption facilities: a systematic review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 14, 161-183.

Khenti, A. (2014). The Canadian war on drugs: Structural violence and unequal treatment of Black Canadians. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(2), 190–195.

Kim, E. T. (2024). “A Drug-Decriminalization Fight Erupts in Oregon”. New Yorker (Jan. 15, 2024)

Kimmel, S. D., Gaeta, J. M., Hadland, S. E., Hallett, E., & Marshall, B. D. (2021). Principles of harm reduction for young people who use drugs. Pediatrics, 147 (Supplement 2), S240–S248.

Kolla, G., Strike, C., Watson, T. M., Jairam, J., Fischer, B., & Bayoumi, A. M. (2017). Risk creating and risk reducing: Community perceptions of supervised consumption facilities for illicit drug use. Health, Risk & Society, 19(1-2), 91-111.

Konnert, S. (2024, March 5). Calls for inhalation spaces grow after 2 supervised injection sites close. CBC.

La Grassa, J. (2023, August 31). As Ontario reviews its drug consumption sites, Windsor still waits for SafePoint approval. CBC News.

Larance, B., Degenhardt, L., Lintzeris, N., Winstock, A., & Mattick, R. (2011). Definitions related to the use of pharmaceutical opioids: Extramedical use, diversion, non‐adherence and aberrant medication‐related behaviours. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(3), 236-245.

Lautenschlager, T. (2023, July 26). Leslieville residents hold town hall on future of safe-consumption site. CBC.

Ledberg, A., & Reitan, T. (2022). Increased risk of death immediately after discharge from compulsory care for substance abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 236, 109492.

Luciano, A. (2024). “B.C. launches opioid treatment phone line to provide access to same-day care.” CBC News (Aug. 27, 2024).

MacLean, C. (2024). New drug testing machines touted by Manitoba government as way to combat toxic drug crisis. CBC News.

Mandryk, H. (2024). Sask. harm reduction workers feeling the effects of 'recovery-based' strategy. CTV News.

Marshall, B. D., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America's first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. The Lancet, 377(9775), 1429-1437.

McDonald, K., Thompson, H., & Werb, D. (2023). 10 key findings related to the impact of Toronto’s Drug Checking Service. Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation.

McNeil, R., Fleming, T., Mayer, S., Barker, A., Mansoor, M., Betsos, A., ... & Boyd, J. (2022). Implementation of safe supply alternatives during intersecting COVID-19 and overdose health emergencies in British Columbia, Canada, 2021. American Journal of Public Health, 112(S2), S151-S158.

Milaney, K., Haines-Saah, R., Farkas, B., Egunsola, O., Mastikhina, L., Brown, S., Lorenzetti, D., Hansen, B., McBrien, K., Rittenbach, K., Hill, L., O’Gorman, C., Doig, C., Cabaj, J., Stokvis, C., & Clement, F. (2022). A scoping review of opioid harm reduction interventions for equity-deserving populations. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas, 12, 100271.

Moman, S. (2024). “Home delivery now available for harm reduction supplies in B.C.” The Abbotsford News (Aug. 7, 2024).

Moran, L., Ondocsin, J., Outram, S., Ciccarone, D., Werb, D., Holm, N., & Arnold, E. A. (2024). How do we understand the value of drug checking as a component of harm reduction services? A qualitative exploration of client and provider perspectives. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 92.

National Safer Supply Community of Practice (NSS-CoP). (n.d.). What is Safer Supply?

O’Brien, D., & Hudson-Breen, R. (2023). “Grasping at straws,” experiences of Canadian parents using involuntary stabilization for a youth’s substance use. International Journal of Drug Policy, 117, 104055.

Office of the Chief Coroner, Ontario. (2023). OCC Opioid related deaths by CSD 2018-2023Q3. [XLSX].

Office of the Provincial Health Officer. (2024). Alternatives to Unregulated Drugs: Another Step in Saving Lives. B.C. Ministry of Health.

Office of the Provincial Health Officer. (2023). A Review of Prescribed Safer Supply Programs Across British Columbia: Recommendations for Future Action. B.C. Ministry of Health.

The Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. Safer opioid supply: A rapid review of the evidence. Toronto, ON: Ontario Drug Policy Research Network; 2023.

Pauly, B., McCall, J., Cameron, F., Stuart, H., Hobbs, H., Sullivan, G., ... & Urbanoski, K. (2022). A concept mapping study of service user design of safer supply as an alternative to the illicit drug market. International Journal of Drug Policy, 110, 103849.

Paun, C., & Hernandez-Morales, A. (2024). Why Portland failed where Portugal succeeded in decriminalizing drugs. Politco (March 28, 2024).

Perry, T. (2024, March 20). Motion to withdraw endorsement of safe injection site defeated. The Daily Press.

Pilarinos, A., Kendall, P., Fast, D., & DeBeck, K. (2018). Secure care: more harm than good. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(41), E1219–E1220.

Pindera, E. (2024). “Indigenous leaders call for addictions help as violence escalates in remote First Nations.” The Free Press (Aug. 18, 2024).

Quon, A. (2024). Experts condemn Sask.'s move to stop providing pipes, limit needle exchanges. CBC News.

Rammohan, I., Gaines, T., Scheim, A., Bayoumi, A., & Werb, D. (2024). Overdose mortality incidence and supervised consumption services in Toronto, Canada: an ecological study and spatial analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 9(2), e79–e87.

Rider, D. (2024). “Reports ordered by Doug Ford government urge fixes, not shuttering of safe injection site.” Toronto Star (Aug. 21, 2024)

Rukavina, S. (2024). Distribution of free naloxone kits skyrockets in Quebec. CBC News.

Russell, C., Ali, F., Nafeh, F., LeBlanc, S., Imtiaz, S., Elton-Marshall, T., & Rehm, J. (2021). A qualitative examination of substance use service needs among people who use drugs (PWUD) with treatment and service experience in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-14.

Russoniello, K., Vakharia, S. P., Netherland, J., Naidoo, T., Wheelock, H., Hurst, T., & Rouhani, S. (2023). Decriminalization of drug possession in Oregon: Analysis and early lessons. Drug Science, Policy and Law.

Salloum, A. (2024). Minister suggests old drug policy 'wasn't working' amid increase in HIV, overdoses. Regina Leader Post.

Salmon, A. M., Van Beek, I., Amin, J., Kaldor, J., & Maher, L. (2010). The impact of a supervised injecting facility on ambulance call‐outs in Sydney, Australia. Addiction, 105(4), 676-683.

Saylors, K. (2024, January 3). SafePoint pause putting lives at risk, advocates say. CBC News.

Schmidt, R. A., Kaminski, N., Kryszajtys, D. T., Rudzinski, K., Perri, M., Guta, A., ... & Strike, C. (2023). ‘I don't chase drugs as much anymore, and I'm not dead’: Client reported outcomes associated with safer opioid supply programs in Ontario, Canada. Drug and Alcohol Review, 42(7), 1825-1837.

Schuckit, M. A. (2016). Treatment of opioid-use disorders. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(4), 357-368.

Slade, H. (2021). Drug Decriminalisation in Portugal: Setting the Record Straight. Transform Drugs.

Slaunwhite, A., Min, J. E., Palis, H., Urbanoski, K., Pauly, B., Barker, B., ... & Nosyk, B. (2024). Effect of Risk Mitigation Guidance opioid and stimulant dispensations on mortality and acute care visits during dual public health emergencies: retrospective cohort study. BMJ, 384.

Smith, A. (2024). “Alberta provides some data on patients using drug addiction treatment centres.” Globe and Mail (July 8, 2024).

Socias, M. E., Grant, C., Hayashi, K., Bardwell, G., Kennedy, M. C., Milloy, M. J., & Kerr, T. (2021). The use of diverted pharmaceutical opioids is associated with reduced risk of fentanyl exposure among people using unregulated drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 228, 109109.

Standards Council of Canada. (2024). The Mental Health and Substance Use Health Standardization Roadmap.

Statistics Canada. (2024). Health of Canadians: Health Behaviours and substance use.

Sterritt, A. (2023). “Toxic drugs killing First Nations residents in B.C. at nearly 6 times the rate of overall population: report.” CBC News (Apr. 21, 2023).

Thomson, E. (2024). “What’s Wrong with Rehab?” Alberta Views (March 1, 2024).

Thunderbird Partnership Foundation. (2024). What Justice Looks Like: Confronting Anti-Indigenous Racism and Building Safe and Comprehensive Mental Health & Addictions Systems for Indigenous Peoples.

Tobias, S., Ferguson, M., Palis, H., Burmeister, C., McDougall, J., Liu, L., Graham, B., Ti, L., & Buxton, J. A. (2024). Motivators of and barriers to drug checking engagement in British Columbia, Canada: Findings from a cross-sectional study. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 123, 104290.

Toronto Public Health. (2018). Quick Facts: Harms Associated with Drug Laws.

Tran, P. (2024). “Lack of public data raises questions about private addiction care in Alberta.” Global News (July 17, 2024).

Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (2021). Decriminalisation in Portugal: Setting the Record Straight.

Tyndall, M., & Dodd, Z. (2020). How Structural Violence, Prohibition, and Stigma Have Paralyzed North American Responses to Opioid Overdose. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(1), E723–E728.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2024). World Drug Report 2024.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2015). World Drug Report 2015.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2024). Developing a risk prediction engine for relapse in opioid use disorder [website].

Vancouver Coastal Health. (2024). Drug Checking.

Virani, H. N., & Haines-Saah, R. J. (2020). Drug Decriminalization: A Matter of Justice and Equity, Not Just Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(1), 161–164.

Wallace, B., van Roode, T., Pagan, F. et al. (2021). The potential impacts of community drug checking within the overdose crisis: qualitative study exploring the perspective of prospective service users. BMC Public Health, 21, 1156.

Wallace, K. (2024). “Ontario is in the midst of a drug crisis. These seven charts tell us who’s being hit hardest”. Toronto Star (April 1, 2024).

Weeks, C. (2024). Ontario overdose deaths reveal gap between health care system and addiction treatment, report finds. The Globe and Mail.

Werb, D., Kamarulzaman, A., Meacham, M., Rafful, C., Fischer, B., Strathdee, S., & Wood, E. (2015). The effectiveness of compulsory drug treatment: A systematic review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 28, 1–9.

Wilhelm, T. (2023, September 22). Deaths, overdoses, and desperation: Here's how bad the opioid crisis is in Windsor-Essex. Windsor Star.

Windsor-Essex County Health Unit. (n.d.). Consumption and Treatment Services Site.

Wood, E., Tyndall, M. W., Lai, C., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2006). Impact of a medically supervised safer injecting facility on drug dealing and other drug-related crime. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 1, 1-4.

Woodward, J. (2024). “Toronto neighbourhoods with drug consumption sites saw many types of crime drop: data.” CTV News (Aug. 28, 2024).

Zavarise, I. (2024). B.C. quietly removes harm-reduction supplies from Fraser Health website. CBC News Vancouver (2024, August 23)