Public Health and Planning Co-creating Green Buildings and Green Streets in Ottawa

THE PROJECT

Ottawa Public Health sought to address environmental health issues such as air pollution, climate change, and extreme heat with land use planning policies by dedicating one staff person from its Health Hazard Response team to the development and implementation of the City’s Official Plan.

BACKGROUND

Located on the eastern boundary of Ontario, Ottawa is the capital of Canada. With over 1 million residents, it is the fourth largest city in the country and the second largest city in Ontario. Residents born outside of the country make up almost 18% of Ottawa’s population.

Ottawa’s economy is built largely around the technology sector and the federal government, but also benefits from a vital rural sector that contributes over $1 billion to the GDP. Ottawa Public Health (OPH), which has responsibility for community health in Ottawa, is a part of the City of Ottawa with a semi-autonomous Board of Health.

THE PROCESS

To address environmental health issues, OPH co-located one staff from its Health Hazard Response team to the Climate Change and Resiliency Unit within the City’s Planning Department for the three years that it took to develop the new Official Plan (OP).

The staff person has a master’s degree in geography with a specialization in environmental sciences and work experience in health hazards, climate change, environmental policy and urban planning. She worked closely with a second OPH staff person, who was also co-located in the Planning Department, who is a registered professional planner with a master’s degree in planning.

“In the Climate Change and Resiliency Unit, I worked alongside two other staff. We were all tasked with embedding climate change into the OP – the most upstream policy that exists within a city planning context.” said Birgit Isernhagen, Program Planning and Evaluation Officer in Health Protection Services with OPH. “We divided the work between us because there is no way one person could do it justice. I focused on heat and health hazards policies while the other two focused on other elements of climate mitigation and resiliency such as energy conservation, emission reductions, flooding, food security and sustainable buildings.”

Birgit was involved in all aspects of the OP’s development. She reviewed, and provided comments from a health hazard and health equity perspective, on every draft of various sections of the OP. She participated in meetings with the staff from other departments, developers, and the public. She also led the development of the OP policies related to extreme heat and worked to ensure that those policies were effectively supported with policy hooks in other sections throughout the OP.

Birgit was also an active participant in the inter-departmental committee that developed a High Performance Development Standard for new buildings. This standard was developed over many months, involved about 30 people with various areas of expertise, and meetings with developers and the public. She played a key role in the standard’s development by chairing a number of sub-groups that were focused on issues such as air pollution, soil volume, equitable access, and sustainable roofing.

“We have learned from past experience that we cannot gain the public health policies we want without participating in every step in the process,” Birgit explained. “There are other experts at the table – hired consultants and staff from other departments – but they are all focused on the issues of concern to them. We had to bring our issues up time and time again to make sure they were not lost or watered down. And we had to be at the table to hear what the other experts were saying to understand how we might collectively meet their needs as well as our own.”

THE OUTCOMES

OPH advanced many public health goals through the OP process, but two (besides the 15-minute neighbourhoods framework that is discussed in a separate case study) stand out as major gains. The new OP, which was passed by City Council in late 2021 and is currently awaiting adoption by the province, now includes a section dedicated to extreme heat.

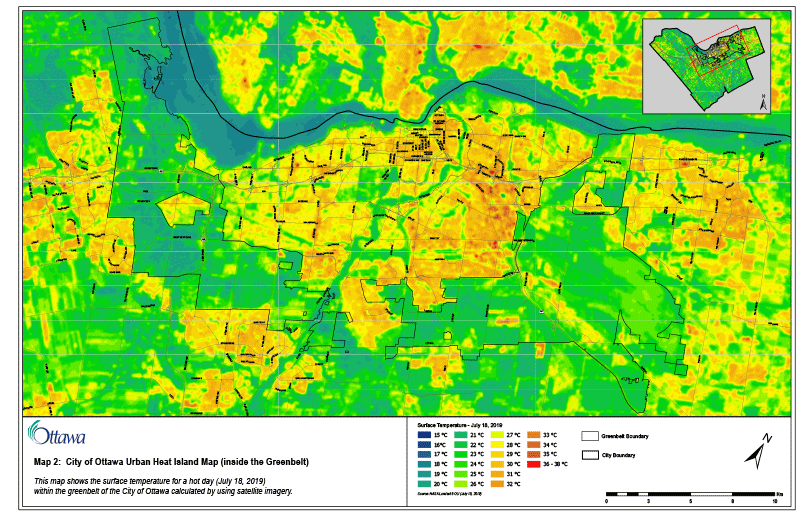

“I don’t believe any other OP in Canada has a section dedicated to extreme heat,” offered Birgit. “We focused on trees, shade, and heat mitigation measures for areas that need them the most. We used the Urban Heat Island maps (City wide, inside Greenbelt) that OPH initiated to support this policy.”

The Urban Health Island maps will also be used as a tool to help inform climate change adaptation strategies, tree planting plans, parks and recreation plans, and health-supportive policies.

The new section 10.3, called “Build resiliency to the impacts of extreme heat”, includes a high-level summary of the health concerns associated with extreme heat and a brief description of the urban heat island effect. It states that: “The built environment should be developed to provide protection against extreme heat, reduce the urban heat island effect, build climate resiliency and safe outdoor recreation and active transportation.”

It includes three mitigation measures that state that:

- Trees will be retained and planted to provide shade and cooling by:

- Applying the urban tree canopy policies in Subsection 4.8 and other sections of the plan;

- Prioritizing them in the design and operation of parks and the pedestrian and cycling networks and at transit stops and stations for users wherever possible; and

- Encouraging and supporting maintenance and growth of the urban tree canopy on residential, commercial, and private property.

- For transit stops where the planting of trees is not feasible, shade structures should be considered subject to funding and available space in the right-of-way in order to provide shelter from the sun as to ensure comfort and transit mobility during extreme heat conditions.

- Office buildings, commercial shopping centres, large-format retailers, industrial uses and large-scale institutions and facilities, shall incorporate heat mitigation measures.

The second major advancement was the authorization and development of a new implementation tool called the High Performance Development Standard. This standard contains a set of mandatory and voluntary measures to advance sustainability, public health and safety, environmental protection, and climate change objectives in the design of new buildings.

“Buildings make up 45% of GHG emissions in Ottawa today. New buildings built today will carry their emissions profile with them for the next 50+ years. Currently, new buildings are constructed following the minimum energy efficiency requirements set out by the Ontario Building Code,” offered Birgit. “New buildings that are built to a higher energy efficiency standard over the next 30 years are expected to account for about 8% of the City’s overall 2050 carbon reduction target of zero emission.”

The new standard is viewed as an effective tool to transform the development industry and build capacity within the sector to integrate sustainability and resiliency into the design of new buildings. Modelled after Toronto’s Green Standard, which is considered the most ambitious standard in the province, Ottawa’s standard uses a tiered approach with mandatory and voluntary components that help raise the minimum design requirements. It also sets the direction for future updates, where the levels of performance advance (e.g. Tier 2 becomes Tier 1), enabling industry to prepare and plan for developments to be higher performing over time.

“The standard will also support improved health outcomes because it requires builders/developers to mitigate potential health impacts for both, the occupants of the building, and residents in the broader community as well,” explained Birgit. “Among the issues that must be considered are access issues for all users, the protection of fresh air intakes from traffic-related air pollution, adequate soil volumes needed to protect long-term tree growth, support for community energy planning, sustainable roofing, and bird safe designs.”

The standard will apply to all projects requiring Site Plan and Plan of Subdivision approval. It will not apply to projects that are applying directly for Building Permits.

LESSONS LEARNED

OPH have identified a number of important lessons from this experience:

- Public health can make significant gains in public policies that support health, health equity, and climate resiliency by engaging fully in land use planning processes.

- With co-location in the Planning Department, public health staff can gain a greater understanding of the processes involved in land use planning to:

- ensure that they are involved at pivotal steps; and

- identify policies that can be strengthened by reframing them as public health issues (e.g., tree protection).

- It helps if the public health staff engaged in these processes have expertise in planning so they understand how to ensure that a policy is effective and what is allowed.

- It also helps if they have specialized expertise relevant to the issues (e.g., transportation, climate change, health hazards) they hope to influence.

- Public health needs to be “at the table” early on so they can understand the issues being raised by other departments, hired experts, and the public, so they can help find ways to meet all of the needs identified as well as bring new ideas to the table.

- It is not enough to bring health evidence to the table; public health needs to develop relationships with the other partners involved and be willing to defend their policies to the public, developers, and City Councillors.

“There were times when the public felt that we did not go far enough on a policy, while the developers felt we were going too far or too fast,” explained Birgit. “Land use planning requires the weighing of many different needs and realities. It does require balancing competing needs and finding solutions that move us forward. If public health is not at the table, we cannot ensure that the policies go as far as they could to meet our public health priorities.”

Prepared by Kim Perrotta, MHSc, Executive Director, CHASE

Last modified: April 20, 2023