Addressing Climate Health in Simcoe Muskoka, Ontario

THE PROJECT

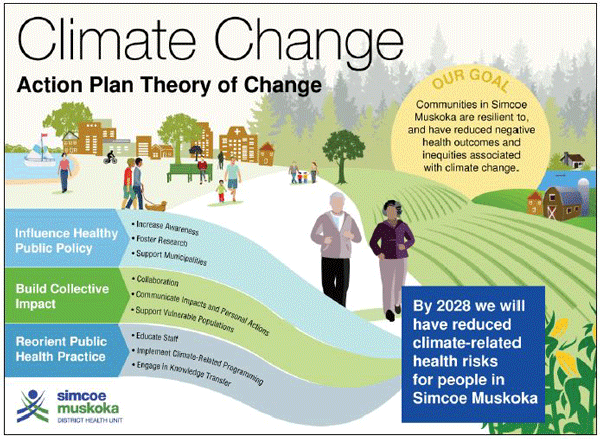

For several years now, the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit (SMDHU) has been working to address climate health guided by a theory of change that incorporates three strategies: reorienting public health practice; influencing healthy public policy; and building collective impact.

BACKGROUND

Located directly north of Toronto, the SMDHU is a local public health agency that reports to an independent Board of Health. SMDHU has responsibility for population health in a fast-growing district that is feeling development pressure for full-time and recreational properties in ‘cottage country’.

SMDHU serves 26 municipalities composed of two upper tier (Simcoe County and District of Muskoka), two single tier (cities of Barrie and Orillia) and 22 lower tier municipalities across rural and urban settings. SMDHU also serves four distinct First Nations communities and urban Indigenous population as well as a defined French-speaking community.

THE PROCESS

Climate change was identified as a priority public health issue in the 2012-2016 Strategic Plan, with the perspective that an agency-wide response would enhance its ability to effectively respond to this important and complex issue. As a component of this work, SMDHU developed a multi-phase climate change action plan, with an initial phase resulting in the completion of a comprehensive climate health vulnerability assessment published in 2017. In 2018, SMDHU developed a theory of change approach to provide a clear focus and direction for ongoing climate change efforts.

Like other health units in Ontario, SMDHU has been challenged to adequately resource climate-health work. Currently, the work is supported by a Climate Change Public Health Promoter position with part-time support from a Program Manager and an Epidemiologist.

“Our ultimate goal is to support a climate-resilient community,” explained Brenda Armstrong, Program Manager for Healthy Environments and Vector-borne Diseases at SMDHU. “When implementing our theory of change, we initially focused on knowledge sharing on climate health among public health professionals and building collaborative actions by establishing a multi-stakeholder committee with partners across our district.”

Internally, staff development on climate health aims to ensure that staff in all programs across the public health unit recognize the health risks associated with climate change, the capacity that people have to protect themselves from climate-related impacts such as floods, extreme heat, and Lyme disease, and the policies and programs that can be used to increase community resiliency to climate change and/or to reduce climate emissions.

“We approached staff development on climate health by learning from previous training for our healthy built environment work and health equity work,” said Armstrong. “We recognized that much of our public health program work increases community resiliency to climate-related impacts, BUT our staff did not recognize it as such. We wanted them to understand climate health; to know how their work was already related to it, and to think about ways their program work could more explicitly or more effectively address it. We want climate change to be seen as a big picture issue that has to be considered in all of our work in the same way that we now do with health equity.”

SMDHU indicated that there is still a lot of work to be done to re-orient its programs internally. The successful integration of climate-health into public health programs and services is ultimately constrained by current public health funding models and provincial program mandates.

“We lost ground with the pandemic,” explains Armstrong. “We all had to drop everything to address COVID-19, and it will take some time before staff return fully to their program areas. But when we do, we want to re-engage with our internal programs to address climate-health vulnerabilities. We want to fold climate health into our thinking in the same way that we have worked to fold the social determinants of health (SDOH) into our work.”

SMDHU also updated its healthy built environment tools to ensure that climate health messaging and actions were clearly and explicitly addressed. Originally developed in 2014, the healthy built environment tools included a Policy Statement Document that provides evidence-based statements that can be used by upper- and lower-tier municipal partners to build healthy community considerations into their Official Plans. In 2018, working with a consultant, SMDHU updated its built environment tools and used this opportunity to apply a climate-health lens to the agency’s built environment work.

“We wanted the policy document and other tools used by staff to include messages and strategies related to climate health as well as chronic disease prevention, injury prevention, health equity, and environmental health,” offered Armstrong. “We want our municipal partners and the public to understand the climate co-benefits of policies and strategies that address issues such as active transportation, greenspace, and parks.”

SMDHU initiated a regional multi-sectoral collaborative network, named the Simcoe Muskoka Climate Change Exchange (CCE). The CCE was developed to address an identified need for local information exchange and collaboration, particularly because SMDHU is not integrated into a regional governance structure. To support the development of the network, SMDHU provided dedicated resources through the Master of Public Health practicum position.

The CCE network now consists of about 40 members representing municipal and local organizational partners (e.g., educational institutions, watershed management and conservation authorities, and hospitals) that are working to address climate change. Key activities include quarterly meetings, educational presentations, peer-to-peer mentoring, collective projects, and development of a regional climate change charter and action framework to support the CCE’s collective efforts.

“The CCE meets formally on a quarterly basis, but there are a lot of informal discussions and collaborations occurring among partners between meetings,” noted Sarah Warren, the Climate Change Public Health Promoter who reports to Brenda Armstrong at SMDHU. “Partners share information about funding opportunities, share educational resources, and leverage the expertise from different organizations on separate and joint projects. A number of smaller work groups have also been created to address issues of common interest.”

SMDHU also invested substantial time into health and policy research related to climate change to inform and support their work and that of other public health agencies across Ontario. Working with the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), they conducted a scoping review to synthesize knowledge on climate-health adaptation strategies and related gaps in the scientific literature to inform public health practice, decision-making, and future research. One component of the project, led by an Indigenous consulting agency, Cambium Indigenous Professional Services, identifies Indigenous perspectives and the importance of including these perspectives into climate adaptation plans. The findings from this work and lessons learned have been captured in a detailed report, a blog published by the National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH), and a journal article published in the Journal of the Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors. They have also been communicated in a webinar and at two conferences.

“The scoping review project, Characteristics of Existing Public Health Climate Change Adaptation Interventions: A Scoping Review, was very big so we have been working to digest and synthesize the findings in smaller reports, journal articles, and presentations that can be shared broadly across the public health sector,” explained Warren. “PHAC commissioned the second piece, Indigenous Lens on Climate Change Adaptation Planning, when the research team recognized that the scoping review did not adequately capture work being done by First Nation, Inuit or Metis (FNIM) Indigenous Communities or organizations. The research team believes that we did not use search terms needed to capture work lead by FNIM Communities and organizations, and that much of this work may not be published in written reports and journals. The next step is to figure out how to apply what we have learned in our everyday practice.”

OUTCOMES ACHIEVED

Despite the challenges, SMDHU continues to make progress on its program. It has:

- Revised its healthy built environment policy document so that it now includes climate-health messaging and strategies;

- Begun climate-health training for its staff;

- Established a very active and effective collaborative between large organizations and local municipalities in its catchment area;

- Prepared two climate-health policy pieces that can be used to inform and support its work in the coming years; and

- Shared the findings from its policy work with the broader public health sector.

LESSONS LEARNED

SMDHU has found that it can employ strategies it used to address new issues such as healthy built environments and frameworks such as health equity to address climate change health risks, resiliency, and action.

They see climate health as an overriding issue that must be considered by staff in all program areas. This requires training of all staff internally, a review and adaptation of internal programs with a climate lens, and the adoption of new policies and programs to address the gaps.

They have learned that there are synergies that can be gained by collaborating across disciplines, organizations, and jurisdictions in a coordinated fashion on community resiliency and climate action. They have found that other organizations in their district have welcomed the opportunity to collaborate and share resources, information, expertise, and opportunities.

They have also learned that if they are to capture the experience and expertise that First Nations communities have to offer on climate change and community resiliency, they must engage directly and respectfully with them.

Prepared by Kim Perrotta, MHSc, Executive Director, CHASE

Last modified: November 25, 2022