What public health workers can do to improve First Nations family health: Dealing with health disparities that arise due to race

Kelly Gibson

There are many different definitions of what a health disparity is, but the general agreement is that “[h]ealth disparities are inequitable and are directly related to the historical and current unequal distribution of social, political, economic, and environmental resources” between different groups of people.1

One health disparity that is currently very prevalent in society is race.

An article from the Canadian Journal of Public Health states well that “[r]ace is often misconstrued as a biological factor; however, it is a social construct that has real biological consequences due to racism and other prejudices in a particular racial or ethnic group.”2 An example of how this is true is in the First Nations peoples in Canada. First Nations peoples report that only 44% are in good/excellent health versus 60% of non-Indigenous people. In addition, First Nations people have shorter lives, and 60% have at least one chronic condition (e.g., diabetes, overweight, arthritis).3 Each of these factors impacts the overall wellbeing and health of First Nations communities as “families are at the heart of health Indigenous communities.”4

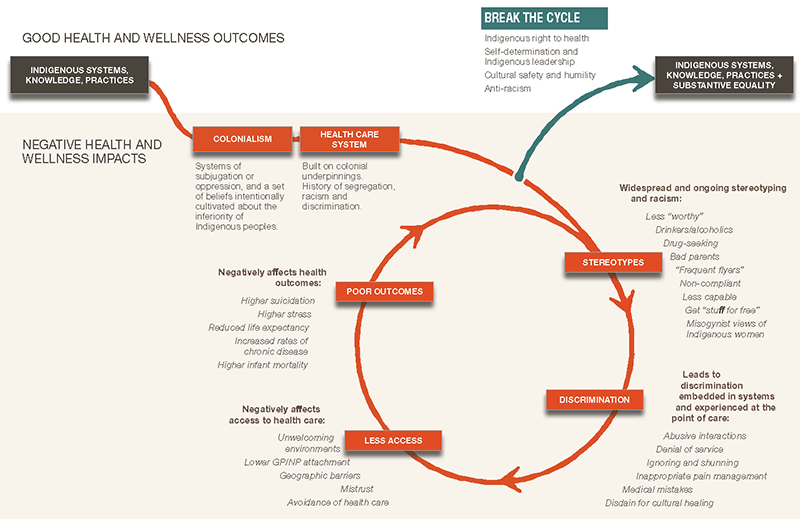

The In Plain Sight report from the Government of British Columbia put together a wonderful graphic that shows the cycle of how health disparities arise and the impact it has on the First Nations peoples health outcomes.

Source: In Plain Sight, 2020

What public health workers can do

Educate yourself

As public health professionals, we are obligated to improve the health of our communities, and that responsibility can be accomplished through participation in webinars, conferences, and courses. However, more diversity training in formal education programs need to be clearly defined and focused to ensure appropriate outcomes and learning.5

Another option is to engage in more community-based participatory research to learn directly from populations about what matters most to them. This includes learning about interventions that they believe would help them.6

Language matters

Second, public health workers need to be aware of the language they use.

“Eliminating” disparities projects the idea that there is a standard to reach; this standard normally is based on the Western-White culture. If we truly want to change health outcomes for all races, it cannot be an all-or-nothing game that “pit[s] communities against one another.”7

For example, small gestures such as learning greetings in traditional languages can give First Nations peoples and families a sense of cultural safety when attending appointments. This may encourage increased health care visits in the long term.6,8

Create accessible health authorities

Finally, public health workers can create inclusive teams that are culturally sensitive to make a more accessible health care setting for individuals and families.

By creating inclusive teams that are culturally sensitive it has been shown that many models, in different locals and settings have led to improved health outcome. In First Nations peoples these outcomes include decreased cholesterol levels, improved quality of life and trauma symptoms, reduced suicides, and decreased all-cause mortality rates.6

Closing remarks

This blog is just one example of how race can impact the health of individuals and families of a certain population. As we have seen in the last five years, First Nations peoples are not the only groups that face these challenges. But the three actions that are outlined here, education, language, and accessible settings, they are proven to be good ways to accept our biases and start to change our ways to reduce the disparity and move towards equity among all!

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

If you are interested in further information about the history of the First Nations peoples journey in Canada, below are a list of some really helpful resources.

- List of Indigenous Health & Professional Organizations in Canada

- Indigenous Corporate Training Inc’s 8 Key Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada pillar blog, with over 620,000 views!

- Indigenous Canada – a 12-lesson Massive Open Online Course from the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta.

- Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future – Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (this is a long one at 535 pages, but a powerful collection of insights from over six years of hearings and testimonies from over 6,000 residential school survivors and families)

REFERENCES

- Health Disparities | DASH | CDC. Accessed February 8, 2023.

- Ezezika O, Girmay B, Mengistu M, Barrett K. What is the health impact of COVID-19 among Black communities in Canada? A systematic review. Can J Public Health. 2023;114(1):62-71. doi:10.17269/s41997-022-00725-6

- Nguyen NH, Subhan FB, Williams K, Chan CB. Barriers and mitigating strategies to healthcare access in indigenous communities of canada: A narrative review. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(2). doi:10.3390/healthcare8020112

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Family is the Focus - Proceedings summary. Published online 2015.

- Dupras DM, Wieland ML, Halvorsen AJ, Maldonado M, Willett LL, Harris L. Assessment of training in health disparities in US internal medicine residency programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2012757. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12757

- Allen L, Hatala A, Ijaz S, Courchene ED, Bushie EB. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CMAJ. 2020;192(9):E208-E216. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190728

- Language Matters: Why We Need To Stop Talking About Eliminating Health Inequities. Health Affairs Forefront. October 2022.

- Jones R, Crowshoe L, Reid P, et al. Educating for indigenous health equity: an international consensus statement. Acad Med. 2019;94(4):512-519. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002476

Post a comment