Addressing Healthcare Inequities in Scarborough

Diane Balkaran

The Toronto district of Scarborough is known for its diversity, comprising 59% new Canadians and 74% who are visible minorities (Scarborough Health Network Foundation, 2024). According to the 2016 census, its top ten immigrant populations include people from China, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, India, Hong Kong, Guyana, Jamaica, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Trinidad & Tobago (City of Toronto, 2019). Unfortunately, health care in Scarborough has been left behind for decades.

I was born and raised in Scarborough, with Guyanese immigrant parents. In 2023, my family had a horrendous experience with the healthcare system when my grandfather — a diabetic and kidney transplant patient with a history of stroke — went to the nearest hospital in Scarborough. The hospital performed some tests and sent him home without informing his family, even though he could barely walk and talk. The morning after, the hospital informed us he should be brought back immediately to be treated for a serious infection and acknowledged that he had been wrongfully discharged. On top of this, the quality of care was poor, with staff having to care for more patients than they could handle. When my grandfather was taken back to the hospital, it was too late, and they informed us that it was indeed the end. Despite him now being a palliative patient, there was no palliative unit where we could freely practice end-of-life rituals in privacy.

There is so much that could have been done differently in this situation. I knew there were health inequities in Scarborough, but this was the first time I had experienced it from the family perspective. I know many other families and friends who have dealt with similar situations within Scarborough hospitals. It made me realize that these healthcare institutions are not adequately designed or resourced to serve Scarborough’s population.

The COVID-19 pandemic illuminated the dire consequences of a consistently underfunded Scarborough healthcare system. Scarborough Health Network (SHN) had more days with patients in intensive care for COVID-19 treatments than any other hospital network in Ontario. It also had the second-highest rate of patients transferred to other facilities due to a shortage of space (Campbell, 2021). Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) accounted for 83% of COVID-19 cases in Toronto, despite making up roughly half the population (Medford, 2023). Working as a clerk in the SHN vaccine clinics, I saw how governments, hospitals, healthcare workers, community organizations and patients scrambled to distribute this vaccine.

Health Inequities

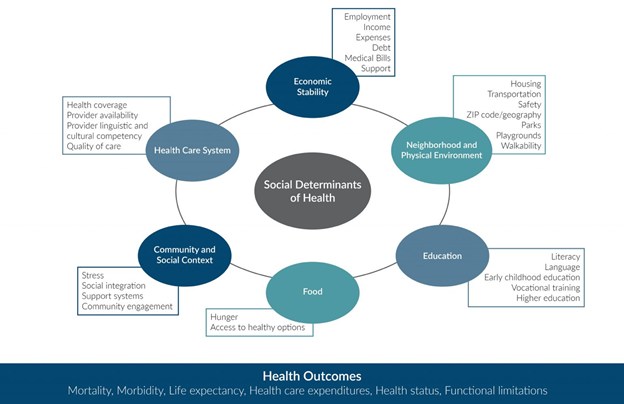

How did Scarborough residents end up in this situation? It comes down to the social determinants of health (see figure below from Social Current, 2024). Social, behavioural, and physical environment factors account for 80% of population health outcomes (Social Current, 2024). Lack of education (often the case for immigrants) leads to unemployment or precarious work, resulting in low income. That in turn increases the likelihood of food insecurity, inadequate housing, and lack of access to quality healthcare. The conditions in which many Scarborough residents live and work also predispose them to diseases that they are not able to treat adequately. Rates of chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and mental health challenges) are higher in this community compared to others in Toronto (Houston, 2023).

Scarborough residents also experience discrimination within the healthcare system, making them less likely to engage with the healthcare system and more likely to experience negative health outcomes due to delayed cancer screenings or treatments (Medford, 2023). There are limited culturally appropriate services, a limited number of diverse healthcare providers, and a limited number of healthcare providers that have built trusting relationships with residents in the community (Campbell, 2021).

It is no coincidence that the needs of Scarborough are neglected. Donations are critical for upgrades, expansions, and new programming within SHN (Lieberman, 2022). Scarborough accounts for 25% of Toronto’s population yet receives less than 1% of Toronto hospital donations (Lombardo, 2024).

The catchment area across the three SHN sites is approximately 850,000 people (Lieberman, 2022). About 15% of Scarborough residents do not have a primary care provider. That is the second lowest number of family physicians per capita in Ontario, and a big part of why emergency departments at its three hospitals operate at more than 200% of intended capacity (Battler, 2023).

These conditions amount to structural inequity/oppression through inadequate funding, resources, and staff provided by the government. They are systemic issues tied to historical and institutional racism that cannot be fixed with short-term or ad hoc solutions (Campbell, 2021).

The Way Forward

Scarborough has demonstrated great resilience. SHN receives more than 176,000 emergency visits annually in ERs built for half that number; does more than 2000 cardiac procedures each year in just two cardiac catheterization labs; performs more than 61,700 surgeries annually in some of the oldest operating rooms across Ontario; and treats more than 6000 chronic kidney disease patients annually for this culturally-prevalent disease on the rise in Scarborough (Scarborough Health Network Foundation, 2024).

Recent major developments offer prospects for addressing these problems. The University of Toronto Scarborough will be opening a medical academy, the Scarborough Academy of Medicine and Integrated Health (SAMIH), in September 2025. At full capacity, it will graduate 44 physicians, 56 physician assistants, 30 nurse practitioners, 40 physical therapists and 300 life sciences students annually (Battler, 2023). One of the program’s objectives is to increase the number of healthcare professionals trained and employed in eastern Toronto (Medford, 2023). SAMIH will partner with the Scarborough Health Network, Lakeridge Health, Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and Michael Garron Hospital, as well as local primary care practices and community agencies throughout the Scarborough and Durham Regions (University of Toronto Scarborough, n.d.).

Scarborough’s healthcare inequities are a stark reminder of Canadian healthcare system challenges. Expanding resources, improving access, and addressing systemic issues can help ensure that all Scarborough residents live healthier, more fulfilling lives.

Recommendations to improve Scarborough’s health system:

- Expand culturally competent healthcare services by:

- Increasing funding and support for local healthcare facilities, including clinics, mental health services, and emergency care.

- Developing mobile health clinics and telehealth services to reach underserved areas and populations.

- Ensuring that healthcare providers are trained in cultural competency to effectively communicate and provide care to patients from diverse backgrounds.

2. Improve health education and promotion in Scarborough by:

- Tailoring health education programs to address the specific health concerns and practices of different cultural groups, ensuring that materials and messaging are culturally appropriate.

- Hosting workshops and seminars on health topics (such as preventive care, nutrition, and chronic disease management), leveraging local health professionals to educate residents.

References

Battler, A. (2023). Why making Scarborough’s health-care system equitable could be a catalyst for change across Canada. University of Toronto Scarborough. https://utsc.utoronto.ca/news-events/our-community/why-making-scarboroughs-health-care-system-equitable-could-be-catalyst-change-across

Campbell, D. (2021). Scarborough’s heavy COVID burden highlights need for better health services in Eastern GTA. University of Toronto Scarborough. https://utsc.utoronto.ca/news-events/our-community/scarboroughs-heavy-covid-burden-highlights-need-better-health-services-eastern-gta

City of Toronto. (2019). Scarborough: City of Toronto Community Council Area Profiles 2016 Census. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/8f7c-City_Planning_2016_Census_Profile_2018_CCA_Scarborough.pdf

Houston, P. (2023). The Scarborough Imperative. Temerty Faculty of Medicine. https://temertymedicine.utoronto.ca/news/scarborough-imperative

Lieberman, C. (2022). ‘Hey, we’re here too!’ Underfunded Scarborough hospitals need donations heading into third pandemic summer. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/8939108/underfunded-scarborough-hospitals-third-pandemic-summer/

Lombardo, C. (2024). Scarborough Health Network embraces its underdog status. Strategy.

https://strategyonline.ca/2024/01/15/scarborough-health-network-shows-its- grit/#:~:text=That%20campaign%20aimed%20was%20to,supporting%20SHN's%20hospitals%20and%20patients.

Medford, M. (2023). A Scarborough solution for addressing racial inequities in health care. Penticton Herald. https://www.pentictonherald.ca/spare_news/article_5d66c683-eea9-5c11-9f3c-9141deb17658.html

Scarborough Health Network Foundation. (2024). Meeting the Needs of Scarborough.

https://www.lovescarborough.ca/

Social Current. (2024). Social Determinants of Health Issue Brief. https://www.social-current.org/reports/social-determinants-of-health-issue-brief/

University of Toronto Scarborough. (n.d.). Scarborough Academy of Medicine and Integrated Health: FAQs. https://www.utsc.utoronto.ca/samih/faqs

Post a comment