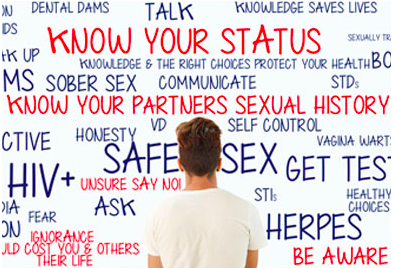

Can you imagine a public health response without signs telling people what to do?

Linda Juergensen

Current Issues in Public Health

On 9 September 2017, following an emotional fact-finding mission on tuberculosis [TB] in Igloolik and Iqaluit, Stephen Lewis concluded: “There is a TB crisis in Nunavut at this very moment…and this is my personal shame…I did not realize that TB was inextricably tied—if I may take a phrase from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission—to a form of cultural genocide.” Lewis, the co-director of AIDS-Free World, and former United Nations special envoy on HIV/AIDS, said he was challenged by colleagues involved in the international movement to eradicate HIV and TB to turn his attention to shortcomings in his own country’s response to TB. Lewis singled out the federal government as ultimately accountable for the state of affairs in Nunavut, but his take-home message was really for all Canadians and those in the field of public health in particular: it is time for “a new era of dignity and respect towards the Inuit.”

TB is preventable and Canada is among the countries with the lowest incidence in the world. Subsequently, Lewis was “startled” to learn that TB is present in over half the communities of Nunavut, and infection rates are 270 times higher among the Inuit (166.2 per 100,000) than in the Canadian-born non-Indigenous population (0.6 per 100,000). Higher rates of TB in the North are largely driven by social determinants of health, including a “devastating” housing crisis and chronic overcrowding, food insecurity, and a perpetual shortage of specialized nursing services.

Persistent rates of infection are also fueled by a deep and long-standing mistrust of Canadian government officials in northern communities complicated by the forced removal of many Inuit from their homelands in the name of public health in the 1950’s and 60’s. Children, mothers, fathers, and grandparents were taken aboard a ‘hospital’ ship for screening and those diagnosed with TB, transported most notably to Hamilton, Quebec City, Toronto and Edmonton where many remained quarantined on the ship or moved to sanatoriums for treatment. Some Inuit were lost to their families for years, and among those whose family members died in quarantine, “to this day, many have never been told where their loved ones are buried.”

What stands out from Lewis’ fact-finding mission is that the disparity in TB rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada align not only with social inequities between the two groups, but vast differences in levels of commitment to acknowledging and working together to address the colonial legacy of poverty and trauma that continues to undermine nation-to-nation relationships and infectious disease management outcomes.

Lewis’ main finding was that “the time has come for all the rhetoric about reconciliation and partnership to be given credence.” Based on the testimony of thousands of Indigenous people forcibly removed as part of Canada’s residential schools project, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded:

Getting to the truth was hard, but getting to reconciliation will be harder. It requires that the paternalistic and racist foundations of the residential school system be rejected as the basis for an ongoing relationship. Reconciliation requires that a new vision, based on a commitment to mutual respect, be developed…Reconciliation is not an Aboriginal problem; it is a Canadian one. Virtually all aspects of Canadian society may need to be reconsidered. (p. 8)

Indigenous Services Minister, Jane Philpott responded to Lewis’ call to action with agreement on the need to work in partnership with Indigenous people in Inuit Nunangat going forward, but “with a very strong focus on the people who are living now with tuberculosis.” How engagement is envisioned in this new partnership for those of us involved in the management of infectious diseases in public health is unclear.

Modern epidemics are commonly referred to as wars: “The War on Ebola”; “The War on SARS”; “The War on AIDS.” From my own practice experience and research with public health nurses involved in the case management of people with HIV in Ontario, it has become evident how viewing the management of an infectious disease as war is tied to the priority given to biomedical and security concerns in Public Health. In a ‘biosecurity’ approach, infectious agents (e.g., HIV, TB) are the enemy, and by extension, people testing positive for an infectious disease, potential threats to the public.

Surveillance is used to identify target groups, and create tailored educational materials and interventions for priority populations to be deployed by nurses working on the frontlines. The goal is to contain the spread of disease. Public health nurses are expected to call all newly diagnosed clients and their contacts, explain the behaviours that pose a risk of transmission, and offer support until they show evidence themselves of being willing and able to ‘protect the public’ from onward transmission. In the cases of reportable infections, like TB and HIV, engagement is mandated by public health law and the flow of knowledge through a health unit is mostly ‘top-down’ and uni-directional. Progress is monitored by epidemiologists and administrators in government health units using prevention and treatment cascades to track the degree to which people from high risk populations conform to a linear pathway that has predetermined for clients what is a measure of ‘good health,’ and in terms of protecting the public, ‘good citizenship’--a serological achievement of an undetectable viral load in cases of HIV. Engagement in the war on HIV/AIDS can arguably be viewed as a form of governmentality.

The focus on biomedical indicators and high-risk behaviours in the public health response has resulted in the development of sophisticated testing and treatment technologies, but it renders invisible the concerns of clients and nurses at the point of care with establishing trusting relationships and addressing social determinants of health. For example, neither stigma nor collaboration are clearly visible as domains of public health on the ‘care cascades’ used to guide and evaluate case management nursing practices in HIV care. Is it not unsurprising, then, that the shortcomings related to how we engage people with HIV are similar to those in the TB response: Canadians with a history of stigma and discrimination are disproportionately affected; there is evidence of geographical and racialized variances in the use of forced measures (e.g. Section 22s and prosecutions for non-disclosure) to mandate compliance with public health expectations; a climate of fear and mistrust has developed and led to the proliferation of anonymous testing sites; and tensions in practice have arisen over who defines what constitutes healthy sexuality and quality of life for people at risk and living with HIV/AIDS (e.g., Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network and Poz Prevention Working Group)? Therefore, reducing the incidence of HIV and TB will not simply be a matter of providing more information and scaling-up testing and treatment services, but also one of critical reflection on the limitations of the current approach used to deliver services.

The findings from my own research in the field of HIV concur with those of Stephen Lewis’ in his fact-finding mission about TB. One of the most pressing issues in the management of TB and HIV in Canada is reconciliation or ‘how can Public Health form more effective partnerships?’ Re-thinking the predominant view that infectious disease management means “war” in public health may be an important starting point, as it would enable us to begin imagining how to work more respectfully and collaboratively within and across jurisdictions with all stakeholders to arrive at solutions that are both sustainable and leave no one behind. But can you imagine a public health response where engagement with clients, colleagues and community partners is not based on telling people what is ‘best’ or what to do? That is what the process of decolonization in the management of TB and HIV might look like.

Post a comment